In this blog we discuss recent Victorian Legislation related to matters of criminal law.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Preliminary Observations

- Serious Offenders Act 2018

- Sex Offenders Registration Act (2004)

- Bail Amendment (Stage Two) Act 2018

- Sentencing Amendment (Sentencing Standards) Act 2017 (VIC)

- Justice Legislation Amendment (Family Violence Protection and other matters) Act 2018

- Justice Legislation Miscellaneous Amendment Act 2018

- Justice Legislation (Police and other matters) Bill 2018

Introduction

Consideration of the impact of the legislation leads to the title of this article.

Increasingly, politicians are determined to impose conditions on their citizens outside of the criminal justice system. Within that system, politicians are determined to force their will on Courts dealing with offenders. All is justified for the protection of the community.

According to an article in the Australian Newspaper on 3 September 2018, Victorian Attorney General, Martin Pakula, was unapologetic about the 60% increase of prisoners on remand since the Bourke Street incident which occurred on 20 January 2017.

“We knew that these changes would increase the remand population and that people would be remanded for less serious offences… It is what the Government intended and what the community expects; to make its safety the highest priority.” – Martin Pakula

The article goes on to say, “a Corrections Victoria spokeswoman said more than 2000 prison beds had opened in the past four years and 1200 more would be available in the next four years.”

Before considering the legislation, we should consider some statistics about prisoners and prison.

The number of prisoners in Victoria as at 30 June 2017 was 7,149. This was an increase of 71% in 10 years (Corrections Victoria). The number of prisoners in July 2018 was 7,836 which is an increase of 10% from the previous year. Of these, 2,851 are on Remand (The Herald Sun, 16 September 2018).

By 1 October 2018, it was estimated that the total number of prisoners would exceed 8,000 (Crime Statistic Victoria).

Currently, 50% of women in prison are on remand (Herald Sun, 14 May 2018).

The number of remand prisoners is expected by the Government to grow by 500 in the next 12 months (The Age, 11 July 2018).

Between 1971-1977, the number of prisoners in Victoria actually decreased in each year (Sentencing Advisory Council). What were we doing differently then?

The cost of housing prisoners in 2016-2017 according to the Office of Corrections was $127,000 per annum. This is $348 per day. Comparatively, the cost of supervising a person on a Corrections Order is $28 per day.

Protection of the community is a fundamental responsibility of any Government. As an outcome or an end this is not open to challenge. However, the Government, and indeed politicians of both major parties in Victoria, blithely justify their policies on the basis of that aim.

What must be questioned is whether gaoling citizens at an increasing rate, both before and during sentence, and, whether supervising them post sentence, is the most effective means to that end.

I would suggest that there are better methods, the most obvious being a greater emphasis on rehabilitation, which in recent years has been relegated in importance as a sentencing outcome.

Preliminary Observations

Before commencing discussion of the legislation, can I make some observations:

1. The seven pieces of legislation are all relevant to practising criminal lawyers.

On a Monday morning, the phone rings and you receive instructions to act on behalf of an accused being interviewed about an alleged aggravated burglary, which involves a sexual assault on a former spouse.

Right there, a number of these Acts are in play – for example, the taking of DNA by police, the applicable principles governing bail applications, standard sentencing, post-sentence supervision, Sex Offenders Registration.

2. Importantly, a number of these pieces of legislation involve detention of citizens other than where sentenced.

Bail involves pre-sentence detention, the Serious Offenders Act involves post-sentence supervision and detention, the Sex Offenders Registration Act involves post-sentence reporting obligations.

And where sentenced, baseline sentences are abolished and replaced with a standard sentence regime. The former is apparently an unworkable form of mandatory sentencing and the latter is apparently not so.

The three Justice Legislation Amendment Acts create or enhance offences against police, emergency service officers and custody officers and call for mandatory minimum sentences in some cases.

3. These trends are cause for reflection about the evolution of our criminal justice system.

Nearly 30 years ago, a man named Garry David was the subject of a piece of legislation directed solely at detaining him indefinitely post-sentence (the Community Protection Act 1990). Mr David had completed his sentence, including his non-parole period, and the government did not want to release him because of his risk of reoffending. The Community Protection Act 1990 gave the Supreme Court power to hold Garry David in preventative detention for periods of 12 months at a time.

This was a cause for heated debate, both within the legal and wider community – the ‘Free Garry David Group’ took to the streets in protest.

This style of legislation must be understood to be totally separate to refusal to grant parole and the indefinite sentence scheme.

The legislative scheme for providing indefinite sentences for serious and dangerous offenders has been in force in Victoria since 1993.

Today, post-sentence detention schemes are justified by governments and accepted by citizens on the grounds of protecting the community. In Victoria, both sides of politics are keen to establish a reputation within the community that they are tough on crime. The importance of rehabilitation has very much taken a back seat to punishment, interestingly justified because community protection is paramount.

Under our current system, 44.8% of persons gaoled return to prison within two years of release. This figure alone establishes that the system is not achieving its aim of community protection. The community is hardly protected if almost half of prisoners released commit sufficiently serious offences to be re-imprisoned within two years.

34% of the prison population are involved in education; 58% of young offenders are expelled from school; and 71% of young offenders are victims of abuse, trauma and neglect.

As criminal lawyers, we need to take the time to reflect on the bigger picture of the criminal justice system beyond our work bubble.

As lawyers working within the criminal justice system, it is our duty to ensure that justice is done, is seen to be done, and that freedoms and liberties are impinged upon only to the extent proven and necessary according to the legislation.

4. We must, however, work within the existing legislative framework.

To do so effectively, we need to consider how we make ourselves aware of legislative amendments and new Acts. Some of the ways we discover changes are as follows:

In criminal law matters, the government of the day often has media releases, usually to demonstrate its tough stance on crime.

- The Law Institute of Victoria sends LIV News which has useful summaries.

- The monthly Law Institute Journal lists new legislation.

- Victoria Legal Aid sends informative emails.

- Sentencing Advisory Council website.

- Judicial College of Law website has excellent resources.

- Social media.

- Speaking with colleagues.

Whatever your method(s), it is important that we have a system in place so that we are confident that we are up to date when advising, instructing or appearing in Court.

The Legislation

Serious Offenders Act 2018

This legislation commenced on 3 September 2018.

In Victoria, a scheme for monitoring serious sex offenders post-sentence was established in the Serious Sex Offenders Monitoring Act (2005).

That Act was expanded on when preventative supervision and detention of serious sex offenders who pose unacceptable risk of reoffending was first set out in the Serious Sex Offenders (Detention and Supervision) Act 2009 which commenced 1 January 2010.

The Harper Review was completed in November 2015.

The Serious Sex Offenders Act 2018 now applies to Serious Sex Offenders and to Serious Violent Offenders.

This Post Sentence Scheme is two-tiered establishing Supervision Orders where offenders generally reside in the community but are supervised and Detention Orders where Courts order that an offender remain in prison at the conclusion of their sentence.

Applications are made by either the Secretary of the Department of Justice and Regulation (for Supervision Orders) and the DPP (for Detention Orders).

The Court must determine whether an offender is an ‘unacceptable risk of harm’ to the community, and if so, make Orders.

The applications proceed in the civil jurisdiction of the Court.

Experience with the sex offenders legislation shows that generally offenders who are subject to these Orders have significant criminal histories with no progress as a result of treatment programs. They often have mental health or personality disorders or limited intellectual functioning.

One would imagine that the same sort of profile will lead to serious violence offenders being placed on either Supervision or Detention Orders. However, there are numerically many more of those offenders in the criminal justice system and the consequences of their offending is often most grave.

A risk of reoffending with grave consequences need only be a low risk for the Courts to accept that it is an ‘unacceptable risk’.

I fear that in the not too distant future, many young men with backgrounds of alcohol and drug abuse who display anger and violence will be subject to these Orders.

Further, such offenders will be different to manage than sex offenders who are often compliant to Orders. I fear that many serious violent offenders will not be able to adhere to Orders on which they are placed.

As lawyers, we must fight hard for these clients who have completed their sentences. In being placed on such Orders, they are losing their liberty in a way that sets them up for future offending if only by breaching the Orders.

Relevant sections of the Serious Offender Act 2018:

S1 of the Act sets out the primary purpose “to provide for enhanced protection of the community by requiring offenders who have served custodial sentences…. and who present an unacceptable risk of harm to the community be subject to ongoing detention or supervision.”

A secondary purpose is to facilitate treatment and rehabilitation.

This legislation defines ‘Serious Sex Offence’ (SSO) in Schedule 1 and ‘Serious Violence Offence’ (SVO) in Schedule 2.

S8 defines which offenders are eligible. They must be over 18 and have a custodial sentence imposed for a serious sex or serious violence offence.

Pursuant to s4, a parolee is deemed to be serving a custodial sentence.

S9(1)(a) provides that the Secretary of the Department of Justice and Regulation has a discretion to make an application for a Supervision Order.

S9(2) if the Secretary considers an application for detention to be made, they must refer that question to the DPP.

S12 provides that the application goes before the sentencing Court, being County or Supreme.

S14 provides that the Court has to be satisfied that the offender will pose an unacceptable risk of committing SSO or SVO if a supervision order is not made.

Pursuant to s14(2) the Court is to have regard to a number of things, generally reports, in determining ‘unacceptable risk’.

Pursuant to s14(2)(b) the Court must not have regard to

- The means of managing the risk

- The likely impact of a Supervision Order on the offender

This means that the Court is simply determining risk.

S14(3) the Court must be satisfied to a high degree of probability that the offender poses or will pose an unacceptable risk.

S14(4) the Court may find unacceptable risk even if the likelihood that the offender will commit an SSO or SVO is “less than more likely than not”.

S31 sets out the core conditions of a Supervision Order (16 conditions)

They include not to commit SSO, SVO or Schedule 3 offences. There are about 50 Schedule 3 offences which include breach of IVO.

Please note that SVO in Schedule 2 includes Recklessly causing serious injury. This brings into play whether or not you try to keep such a charge in the Magistrates’ Court.

S32 sets out intensive treatment and supervision conditions.

S34 gives power to the Court to impose a condition as to residence, including whether the offender is to reside at a residential facility.

S35 sets out suggested conditions for the Court.

S41 provides that the Court can declare restrictive conditions.

Part 4: Be aware that there are powers for the Secretary to apply for Interim Supervision Orders.

Part 5: Detention Orders

Part 7: Emergency Detention Orders

S169(1) Created the offence of contravening a condition of a Supervision Order or an Interim Supervision Order. (Level 6 Offence – 5 years Imprisonment)

Note: S10AB of the Sentencing Act 1991 which prescribes that:

- A Court must impose a term of imprisonment of not less than 12 months unless the Court finds under section 10A that a special reason exists

- Subsection (1) applies only if the court is satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the offender intentionally or recklessly contravened a restrictive condition of the supervision order or interim supervision order.

In summary, the Court must be satisfied (i) to a high degree of probability (standard of proof) that (ii) the offender poses an unacceptable risk (test of unacceptability).

What is a ‘high degree of probability’?

It is less than beyond reasonable doubt but greater than the balance of probabilities.

What is an ‘unacceptable risk’?

Nigro v Secretary to the Department of Justice [2013] VSCA 213:

[7] “The test of unacceptable risk does not require a particular degree of risk. It need not necessarily be more likely than not. The lower likelihood of risk stated in s 9(5) is not to be confined to a particular category of offence.”

[113] It is clear that the Act contemplates that some level of risk is acceptable in a democratic society that values the rights of an individual to freedom and privacy. As we have said, it involves a balancing of the nature of the risk and the likelihood of its occurrence against the fundamental value which society accords to individual liberty.

This means that the offender does not have to be found to be no risk of reoffending to avoid an Order.

In [116] the Court adopted what the Minister for Corrections said:

“in some cases the gravity and nature of the possible offending may satisfy the judicial officer ‘that even a small likelihood of reoffending is an unacceptable risk and sufficient to warrant the imposition of a detention order or supervision order’”

This means that where the potential offence will have grave consequences, the likelihood or risk of the offender committing the offence need only be low to be an ‘unacceptable risk’.

[117] “To prescribe what degrees of risk may or may not be unacceptable would remove the test of its necessary flexibility. The legislature has deliberately selected a threshold test that does not specify a particular degree of risk. Rather, the test requires an assessment of the risk and a consideration of the nature and gravity of the relevant offence and the magnitude of the harm that may result having regard to the manner in which the offender had previously committed such an offence. It is the combination of these factors that will determine whether the risk of occurrence is of a sufficient order to make the risk unacceptable.”

Sex Offenders Registration Act 2004

This Act commenced on 1 October 2004. The amendments we are discussing commenced on 1 March 2018. Separately, the travel restriction legislation commenced on 13 December 2017.

Section 1 sets out the purposes of the Act and includes:

(a) to require certain offenders who commit sexual offences to keep Police informed of their whereabouts and other personal details for a period of time –

(i) to reduce the likelihood that they will reoffend, and

(ii) to facilitate the investigation and prosecution of any future offences that they may commit.

The Act sets out a regime where accused who are found guilty of certain offences, become Registerable Offenders and are either automatically or via exercise of Court discretion, placed on the Sex Offenders Register for a minimum period of time.

Pursuant to Section 6, it applies to persons who have committed certain offences after 1 October 2004.

The purpose of this part of the paper is to discuss recent amendments which revolve around the suspension from reporting obligations.

(1) – Section 39(1)

This is not a recent amendment, and has been in the Act for a number of years.

Pursuant to Section 39(1), a person who is obliged to report for life, can apply to the Supreme Court for an Order suspending their reporting obligations.

Pursuant to Section 39(2), the person must have been on the Sex Offenders Register (‘SOR’) for a minimum of 15 years. As this Act was operational from 1 October 2004, no one has made 15 years on the Register and therefore no one has made application to the Supreme Court.

(2) – Sex Offenders Registration Amendment (Miscellaneous) Act 2017

These amendments came into effect on 1 March 2018.

They offer some relief to the 4,000 active persons on the Victorian SOR.

The relevant amendments are as follows:

s 11A This amendment is the government keeping good its promise to give young offenders the opportunity to avoid being placed on the SOR.

A person who was 18 or 19 years of age at the time of committing a registerable offence can apply for a Registration Exemption Order. Under the Application, a Court may declare that the Applicant is not a registerable offender if it is satisfied of a number of matters set out in Section 11B, including:

(1)(a)(i) That the victim was 14 years or older during the commission of the offence.

(1)(b) That the Applicant poses no risk or low risk to the sexual safety of one or more persons or the community.

s 11C This section sets out the time limits for applications.

They may be made not later than 6 months after receiving notice of reporting obligations, which is usually the date of sentence.

In fact, they made be made on the day of sentence.

For people already on the SOR, they may make application up to two years after 1 March 2018.

The documents filed with the Court must be detailed and strictly comply with Section 11A.

s 11F This section sets out that the Chief Commissions of Police is to be a party to an application.

Where there have been successful applications under Section 11A, they have invariably involved the support of the Chief Commissioner.

s 45A(1) Section 45A(1) gives the Chief Commissioner power to suspend reporting obligations for a period not exceeding 5 years.

Section 45A(3) sets out the matters which the Chief Commissioner must take into account in determining whether to suspend a person’s reporting obligations.

Pursuant to Section 45A(2), the test is the same as that set out in Section 11B(1)(b) – “Not pose a risk or poses a low risk.”

Prior to these amendments, the Chief Commissioner could suspend the reporting obligations for up to 12 months.

Further, prior to the amendments, the Chief Commission applied a test of a person posing no risk, rather than the current test of no risk or low risk.

Under the Act, the powers of the Chief Commissioner are delegated to a Superintendent, generally with the Sex Offenders Registry.

In our office, we have had a number of persons on the SOR making enquiries regarding applications under Section 45A, however the officers at the Sex Offenders Registry have stated that these applications are generally made by the compliance manager of the person on the Register, and supported with medical evidence.

The interpretation of the Sex Offenders Registry as to how this discretion should operate is that it applies to persons who are either cognitively or physically impaired to the extent that it can easily be demonstrated that they pose no risk or a low risk to the community. The applications made by compliance managers have been where the person on the Register is bed-ridden in a nursing home or suffering dementia for example.

Further, the view of the Sex Offenders Registry is that the discretion ought not be used for people of low risk with a long history of compliance. If a person has the physical and cognitive ability to comply with their reporting conditions, there is no need to assess them for suspension, because they can comply.

This is an unfortunate interpretation, but where the discretion lies with the Police, it seems it will be very difficult to change their view.

Risk assessment tool used by Sex Offenders Register is ‘Static 99’.

(3) – Passports Legislation Amendment (Overseas Travel by Child Sex Offenders) Act 2005 (Cth)

This Act amended the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), on 13 December 2017 – just before Christmas last year.

It requires registered Sex Offenders to obtain permission from a competent authority to travel internationally. In Victoria, the competent authority is the Sex Offenders Registry. Essentially the Sex Offender’s passport is cancelled and they must apply for a travel document which allows them to travel.

The Act creates a criminal offence to travel overseas unless a competent authority has given permission for the person to leave Australia.

So, Victorian registered offenders apply to the Victorian Sex Offenders Registry.

How is the discretion to grant permission to leave to be applied?

According to the Second Reading Speeches, there are 20,000 Registered Sex Offenders in Australia. 2,500 are added each year, and 770 went overseas in 2016.

Further, whilst there is a blanket ban on travel, there is an exception if a person can show good reason. Under the legislation, the discretion lies with the competent authority.

It is being interpreted to mean that there must be exceptional or extraordinary circumstances for the SOR to grant a travel document.

This restriction on travel is having a major impact on persons on the register, many of whom regularly travel overseas and have done so for years. Pursuant to this legislation, they now cannot travel.

In our experience, examples of persons being granted permission to travel include the death of a family member overseas or business where the presence of the applicant is essential.

This legislation is being applied very strictly and it might be best to contact clients on register and advise accordingly. Many people who apply to travel are completing the application online without understanding that they have to show exceptional circumstances.

Bail Amendment (Stage Three) Act 2018

This is the third piece of legislation redrafting Bail law in Victoria.

The Bail Amendment (Stage One) Act 2018 came into force on 21 May 2018. The Bail Amendment (Stage Two) Act 2018 came into force on 1 July 2018. The Bail Amendment (Stage Three) Act 2018 came into force on 1 October 2018.

It is the most major reform to Bail in Victoria since 1977, and I think it best here to consider the totality of all stages as one act, the Bail Act 1977.

Essentially it is the structure of the Act unchanged, although the core of the Act, Section 4 (entitlement to bail), is rewritten.

We will discuss a practical guide to applying for bail.

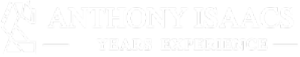

1. First, determine into which category the charge(s) your client faces, fall. This will determine the applicable threshold test for granting bail.

Under the new regime, all offences fall into one of three categories: Schedule 1, Schedule 2 or non-Schedule. The Schedules appear at the back of the Act.

Be aware of uplifting clauses within the Schedules.

Confirm your analysis with the Prosecutor.

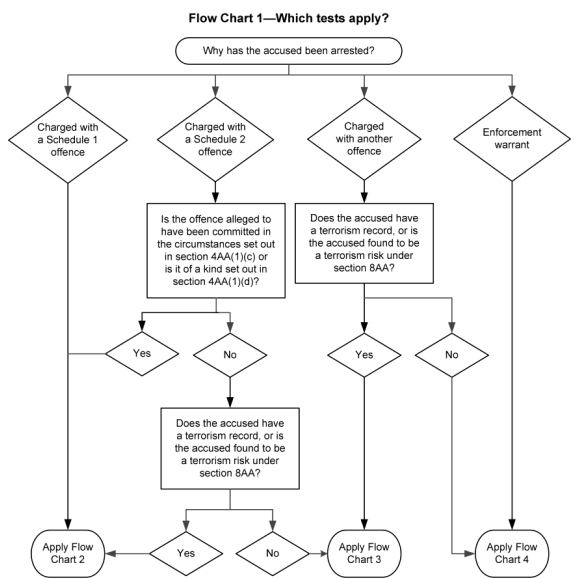

2. You have decided that you face a Schedule 1 offence.

Pursuant to Section 4A, the Applicant must show that exceptional circumstances exist for bail to be granted.

The definition of ‘exceptional circumstances’ is unchanged by the Act.

However, pursuant to Section 4A(3), the bail decision maker must take into account the ‘surrounding circumstances’, which are set out in a non-exhaustive list in Section 3AAA(a)-(m).

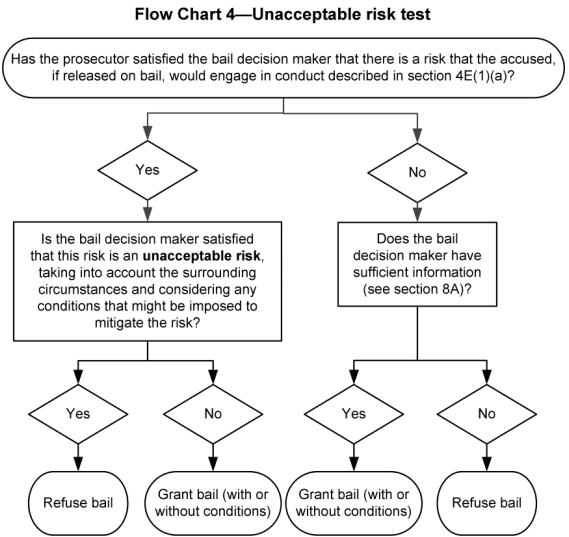

3. If the Applicant has shown exceptional circumstances, pursuant to Section 4D, the bail decision maker must then separately consider whether the Applicant represents an unacceptable risk such that bail should be refused.

The Prosecutor bears the burden of satisfying the existence of risk that the Applicant would do one or more of the matters raised in Section 4E, and that that risk is unacceptable.

Section 4E does not change the risks to be considered, however, pursuant to Section 4E(3), the bail decision maker in considering whether a risk is an unacceptable risk, must take into account the surrounding circumstances set out in Section 3AAA.

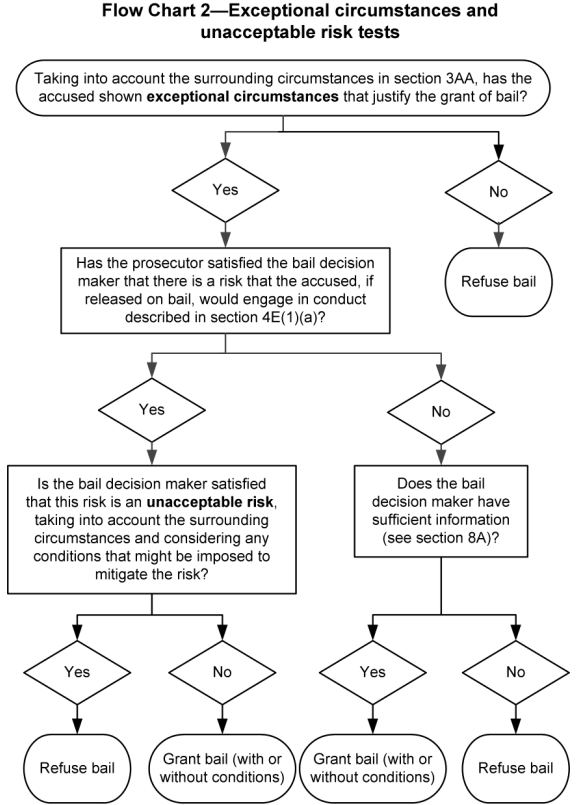

4. You have decided that you face a Schedule 2 offence.

Pursuant to Section 4C, the Applicant must show that compelling reason exists for bail to be granted.

‘Compelling reason’ is the term which replaced the old ‘show cause’ test, and is not defined in the Act.

However, pursuant to Section 4C(3), the bail decision maker must take into account the ‘surrounding circumstances’, which are set out in a non-exhaustive list in Section 3AAA(a)-(m).

5. If the Applicant has shown compelling reason, pursuant to Section 4D, the bail decision maker must then separately consider whether the Applicant represents an unacceptable risk such that bail should be refused.

The Prosecutor bears the burden of satisfying the existence of risk that the Applicant would do one or more of the matters raised in Section 4E, and that that risk is unacceptable.

Section 4E does not change the risks to be considered, however, pursuant to Section 4E(3), the bail decision maker in considering whether a risk is an unacceptable risk, must take into account the surrounding circumstances set out in Section 3AAA.

6. If the Applicant is charged with a non-scheduled offence there remains a presumption for bail to be granted, unless the Prosecution can show that the Applicant represents an unacceptable risk.

An interesting issue arises from the circuitous consideration of ‘surrounding circumstances’. Under the Act, in determining whether exceptional circumstances or compelling reason exist, the bail decision maker has to take into account all of the surrounding circumstances. Separately, in determining whether an unacceptable risk exists, the bail decision maker has to take into account all of the surrounding circumstances.

Under the old Act, defence lawyers commonly argued that if, taking into account all of the surrounding circumstances, there was not an unacceptable risk of committing an act set out in the new Section 4E, then in reality, the Applicant had ‘shown cause’ why it was not justified to hold them in custody.

The new Act directs a two-step process which says that the bail decision maker must first find exceptional circumstances or compelling reason before consideration of unacceptable risk.

However, the question must be asked whether, if the Applicant can show that he is not an unacceptable risk, that in reality, they have shown compelling reason.

‘Compelling Reason’ is not defined in the act but has been considered in the recent decision by Appeal Justice Beach in Re Ceylan [2018] VSC 361 at:

[46] “For an applicant required to show ‘compelling reason’, a synthesis or balancing of all relevant matters must compel the conclusion that the applicant’s detention in custody is not justified.”

[47] “While one must be careful not to substitute other expressions for the language used in the Act, compelling reason would likely be shown if there existed forceful, and therefore convincing, reason showing that, in all the circumstances, the continued detention of the applicant in custody was not justified. It is not, however, necessary for an applicant required to show compelling reason, to show a reason which is irresistible or exceptional… ‘compelling reason’ in s 4(4) of the Act might appropriately be described as reason which is difficult to resist.”

Some other important sections of the Bail Act 1977 (reprinted as at 1 October 2018).

s 1A Sets out the purpose of the Act and refers to whether a person ‘accused of an offence’ should be granted bail. Section 4 also speaks of a person ‘accused of an offence’.

The old Section 4(1)(c) has been repealed. This was the subsection that allowed Courts to grant bail to persons awaiting sentence after having been convicted.

Limiting the Act to persons accused of an offence has implications. For example, where an accused is found guilty but not yet sentenced (or after pleading guilty at arraignment for a later plea?), how is bail extended.

We need to rely on Section 101 of the Sentencing Act 1991:

- The sentence for an offence may be imposed in open court at any time and at any place in Victoria.

- The judge or magistrate presiding at the trial or hearing of an offence or receiving a plea of guilty to an offence or any other judge or magistrate empowered to impose sentence may, when he or she thinks it desirable in the interests of justice so to do and from time to time if necessary—

- fix, or indicate by reference to a fact or event, the time; and

- fix the place—

at which the sentence is to be imposed.

- The judge or magistrate who is to impose sentence for an offence may—

- release the person to be sentenced on the person giving an undertaking conditioned for that person’s attendance at the proper time and place; or

- make an order or orders for the removal in custody of that person from one place in Victoria to another.

- This section does not take away from any power possessed by a judge or magistrate under statute or at common law.

s 3D

s 5AAAA The Act directs that where the bail decision maker is dealing with an accused charged with a family violence offence, they must consider the risk that the accused would commit family violence. Such a risk would already be considered within Section 4E, but the decision maker must consider imposing a condition or making a Family Violence Intervention Order.

s 5AAA Sets out how a bail decision maker determines conditions that are appropriate.

Sentencing Amendment (Sentencing Standards) Act 2018

The Victorian Government reacted to decision in DPP v Walters 49 VR 356 (17 November 2015) which found that the baseline sentencing regime was “Incapable of being given any practical operation”.

It therefore introduced a Standard Sentencing Scheme for offences committed after 1 February 2018.

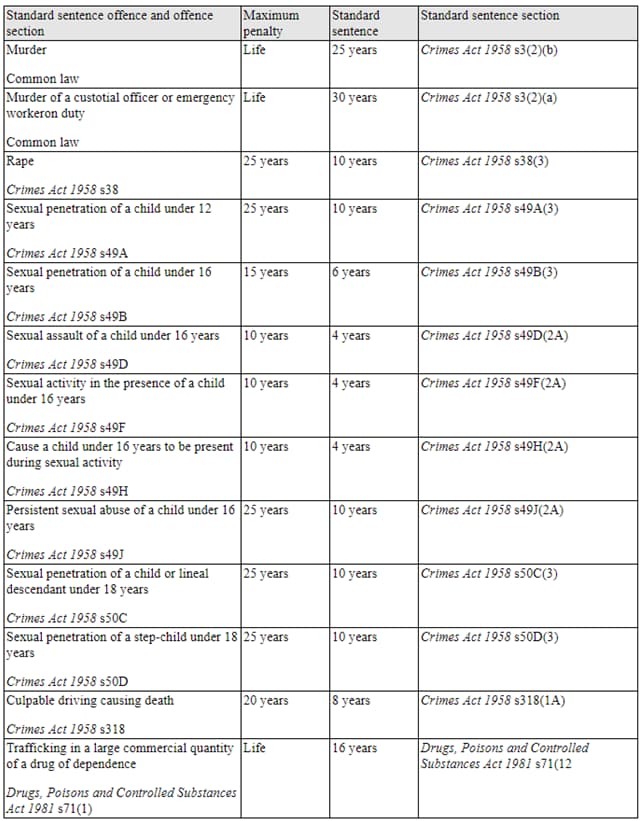

There are 13 standard sentence offences and these are set out in the table below:

Source: Judicial College of Victoria

The Act sets out standard sentences for those offences and fixes non-parole periods.

Standard sentence is calculated at 40% of the maximum penalty for the offence.

Relevant Sections of The Sentencing Act 1991:

s 5A Standard Sentence Scheme

s 5B Sentencing for Standard Sentence Offence

s 5B(1) Exceptions to the Standard Sentence Regime

- If the offender was under the age of 18

- If the offence is determined and heard summarily

s 5B(2)(a) Standard sentence is one of the factors relevant to sentencing

s 5B(3)(a) Subsection (2) does not limit matters Court can take into account.

s 5B(3)(b) Not intended to affect instinctive synthesis

s 11A Fixing of non-parole period for Standard Sentence Offence

- The non-parole period is 30 years if life offence.

- 70% of the term imposed where that is over 20 years.

- 60% of the term imposed where that is less than 20 years.

Note: The exception that the Scheme does not apply to matters triable summarily is important and we need to tactically consider how we run our cases.

Justice Legislation Amendment (Family Violence Protection and other matters) Act 2018

This legislation mostly came into force on 15 August 2018.

In short, the Act will introduce a Specialist Family Violence Court Division in the Magistrates’ Court, enables applications for family violence intervention orders to be filed online and abolishes appeals against interim intervention orders.

Further, complainants in family violence offences may make a recorded statement for use as their evidence-in-chief in a proceeding. These may also be used as evidence in proceedings for a family violence intervention order as well as in other proceedings, by court or tribunal order.

Currently, adult respondents to Final Family Violence Intervention Orders in certain postcodes face court-mandated Men’s Behaviour Charge Program as part of a counselling order regime. These amendments expand the reach of this program such that Courts will be able to make Orders regardless of where the respondent resides.

Justice Legislation Miscellaneous Act 2018

This piece of legislation came into effect on 25 September 2018.

Custodial sentences & Special reasons

Introduces custodial sentences for injury offences against emergency workers by adding those offences to the definition of ‘Category 1 offence’ in the Sentencing Act 1991. ie, the Court cannot impose a Community Corrections Order or other non-custodial sentence, unless special reasons are present.

Aggravated home invasions, Aggravated carjacking, Culpable driving causing death and some armed robberies are also made a ‘Category 1 offence’ with the same effect on sentence.

‘Special reasons’ is curtailed to “address concerns by government and the community that these laws are not being applied as intended by the courts, and to provide additional clarification and guidance to Courts…”

This includes that self-induced intoxication cannot be relied upon with respect to impaired mental functioning, and that persons aged 18 or 19 can no longer rely on psychosocial immaturity as a special reason.

Criminal Procedure amendments

Codification of Basha hearing (new section 198B)

Justice Legislation (Police and Other matters) Bill (19 June 2019)

Will come into effect in June 2019.

The definition of an ‘emergency worker’ is in s10AA(8) of the Sentencing Act 1991.

Police DNA Powers

Under this Act, Victoria Police will be empowered to take DNA samples from persons suspected of committing, or found committing, an indictable offence. It introduces a new class of procedure called a ‘DNA profile sample’. Police can perform this procedure without having to seek a Court Order. Further, if the suspect consents to the giving of the DNA sample, the procedure can be undertaken without that person being placed under arrest.

PSOs and PCOs

New offence (s 31C Crimes Act 1958) of discharging a firearm when reckless to the safety of a police officer or a PSO – an offence which carries a maximum of 15 years imprisonment.

New offence (s 31D Crimes Act 1958) of intimidation of a police officer etc, where the intimidation (reasonable expectation to arouse apprehension or fear in the victim for their safety) relates to the victim’s status as such an officer or a familial relationship – an offence which carries a maximum of 10 years imprisonment. The offence does not seek to target “low level antisocial language or behaviour.”

In the case of Common Assault, new section 320A Crimes Act 1958, increases the maximum penalty where the offence is aggravated by it being committed with an offensive weapon readily available and the victim is a Police officer or PSO on duty. The penalties are a maximum 10 years imprisonment, or 15 years where the offensive weapon is a firearm.

Commercial drug trafficking

Under the Criminal Organisations Control Act, ‘Large commercial’ quantities are introduced for drug trafficking in 1,4- Butanediol (and similar), lifting the penalties where the amounts are in excess of 20kgs to life imprisonment.

For heroin, the large commercial quantity are reduced from 750g to 500g of pure substance and 1kg to 750g for mixed. Commercial quantities are reduced from 250g to 50g for pure substance and 500g to 250g for mixed.

It introduces the offence of trafficking in a commercial quantity a drug of dependence at the direction, or for the benefit, of a criminal organisation. It carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.